Mothers

are experts in the knowledge of their children's bodies, in their

medical histories, and in their daily practices, which are part of what

forensic sciences call antemortem information.

By R. Aída Hernández Castillo (CIESAS-GIASF)

Photographs: Social and Forensic Anthropology Research Group (GIASF)

In the last two years I have joined the walk of organizations

of relatives of the disappeared, constituted mainly of mothers and

wives, who, faced with the inability of the Mexican State, have taken

on the task of searching for the human remains of their relatives in

clandestine graves.

As happened with the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, or with the

Mutual Support Group in Guatemala, it is mostly mothers who have

mobilized in the search for their children, politicizing their maternal

identities to transform all the disappeared men and women into their sons

and daughters.

The labeled T-shirts used in the marches or in the search days have

changed from "I will look for you until I find you" to "We will look

for them until we find them."

Their identity as "mothers" has been politically mobilized in order to obtain

the solidarity of civil society and the logistical support of local

institutions in the face of what they consider a "relative protection" of organized crime groups that control the area. (1)

She was convinced that if she had been allowed to touch her son's skull, she would have been able to recognize it with touch. "My fingers know every inch of that head. I've seen him and felt transformed since I first took him in my arms when he was born. You do not know how many times I stroked his head when he leaned on my legs," she argued.

When I shared this story with a forensic physical anthropologist

colleague, she smiled incredulously at what seemed to be a more

sentimental anecdote about the stories of relatives of the disappeared.

The conviction of the mother and the disbelief of the physical

anthropologist made me reflect on the hierarchies of knowledge that

have been established in the forensic field and on the need to recognize

the knowledge and experiences of the relatives in any project of truth

and justice that can be promoted.

In the historical moment that we are living in Mexico, where some

spaces for the search of justice seem to be opening up, it is a priority

to listen to those who have more experience in the search and finding

of disappeared persons: family organizations.

Faced with the temptation to export models of transitional justice that

do not consider the historical, cultural, and regional specificities,

the local knowledge of the relatives is fundamental not only for the

search and identification of the disappeared, but also for the

development of alternative forms of transformative justice.

As academics committed to social justice, we have the responsibility to

confront the hierarchies of knowledge that have been established with

the so-called "forensic turn" (2) that has institutionalized a pyramid

of knowledge that has genetics at the top, followed by physical

anthropology and archeology; and in the lower part of the pyramid the

social sciences.

Scientific knowledge has been imposed on the local knowledge of

relatives, who are seen as mere "testimonies of secondary victims."

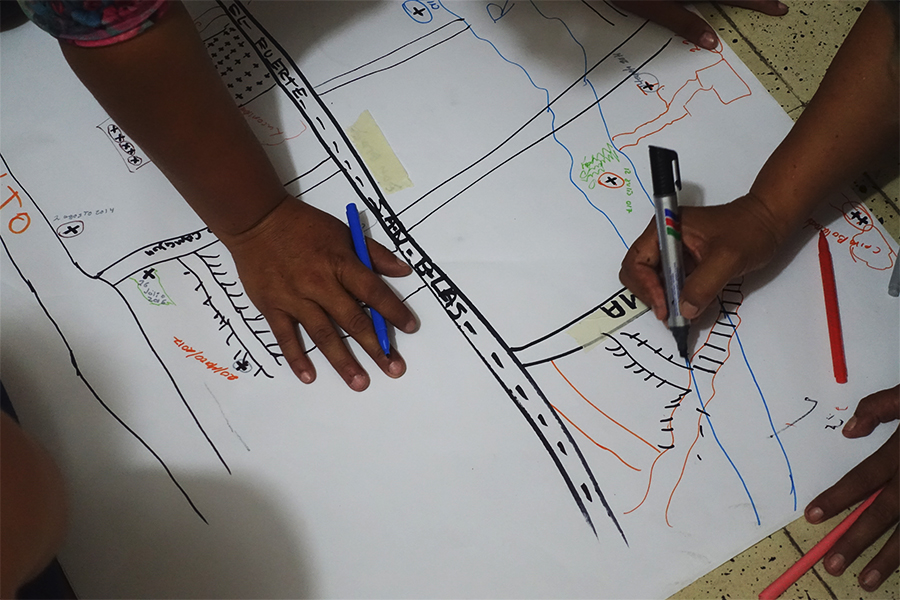

In our experience working with an organization of mothers and wives of

the disappeared known as Las Rastreadoras del Fuerte, we have carried

out Memory Workshops that have been fundamental for the documentation of

their findings and the subsequent georeferencing of the graves they

have found.

These spaces have allowed us to recognize the deep knowledge that the

members of this organization have, not only of the physical geography of the North of Sinaloa, but also of the political and social context that

enables and reproduces violence. On top of the creation of maps, knowledge has been shared about the origins and manifestations of the different types of violence in the

territories.

Appropriating the forensic knowledge obtained in the multiple spaces of

confluence and formation of the movement of relatives of the

disappeared, and using their local knowledge about the geography of

violence, Las Rastreadoras have begun to destabilize the hierarchies of

knowledge established by the "forensic," legitimizing their own

knowledge.

Only from a respectful dialogue that recognizes different

experiences and knowledge, as well as the different ways of being and occupying space in the world, and the different ways of imagining justice, can we

contribute to the construction of a comprehensive and inclusive peace

agenda that our country so urgently needs.

*

The Research Group in Social and Forensic Anthropology (GIASF) is an

interdisciplinary team committed to the production of socially and

politically relevant knowledge about the forced disappearance of people

in Mexico. In

this column, Con-ciencia, members of the Research Committee and

students associated with the Group's projects participate (See more: www.giasf.org )

(1) This position assumes the existence of some kind of ethical-moral

reserve in the perpetrators of violence, who will respect the figure of

the mother.

However, the "pedagogy of terror" has crossed all ethical and moral

limits. Respect for "the Mexican mother" is no longer part of the code of the assassins, nor of the security forces with which they

are colluded.

The mothers of the disappeared are at the center of the violence, as

shown by the murders of Marisela Escobedo in Chihuahua, Sandra Luz

Hernández in Culiacán, Miriam Rodriguez in Tamaulipas, and Cornelia San

Juan in the State of Mexico, to name the best known cases.

(2)

The term in English that has popularized is "forensic turn." Ror a critical reflection on this paradigm, the work of

the Spanish anthropologist Francisco Ferrandez in

politicasdelamemoria.org can be consulted.

Completely sad and heartbreaking... these mothers need some form of closure... that final last touch of their loved one.... maybe this is the story of the drug war people do not want to acknowledge and live in denial about...

ReplyDeleteGC