By "El Huaso" for Borderland Beat

|

| Thumbnail image created with the help of AI. |

When we think of criminals, we often imagine shadowy figures, operating in the dark away from government scrutiny and public view as they steal, rob, and kill. As many scholars have pointed out, the Mexican organized crime landscape overturns this idea, as Mexican criminal groups are obsessed with public communication with the government, civilians, and other criminal groups.[1] They use these messages to influence how they are perceived by civilians, threaten, and coerce the government, and accuse rivals of heinous acts.

However, few attempts

have been made to consistently quantify and measure the usage of narco messages

by criminal groups. This article attempts to find out how many narco messages

are left across Mexico each year, based on a review of the few large scale

narco message collections publicly available. I will examine each of these

datasets, explore their definitions and methodology, and attempt to estimate

the number of narco messages left in Mexico each year.

In the 2000s, physical communications from criminal groups burst onto the scene. Criminal groups such as the Zetas used banners hung from bridges in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas to recruit members, offering them better pay and food.[2] Other criminal groups like La Familia Michoacána used messages to provide explanations for violent attacks, such as a 2006 banner calling victims of beheading recipients of “divine justice”.[3]

Zetas narco banner in Nuevo Laredo, 2008.[4]

A US counter narcotics official interviewed by Reuters in 2008 said that narco messaging would eventually disappear, saying “Drug traffickers are not stupid, they know that if they cause chaos, the military will come. It is not like the old Mexico. They know that too much attention is bad for business.” [5] However, that was not the case, as narco messages expanded geographically and proliferated numerically. Narco message researcher Dr. Philip Luke Johnson wrote the first narco message appeared in 2004 and by 2008 narco messages have been found in 28 of Mexico's 32 states.[6] Another scholar, Dr. Laura Atuesta, found that between 2007 and 2011, the number of narco messages found in Mexico increased 1,611%.[7]

These messages take the form of scripted narco communication videos, filmed executions, and tortures, large printed narco banners, and most common of all, physical narco messages left on cardboard posters. There have only been a few studies which have attempted to quantify the usage of narco messages. This post will not examine the content of the studies, though they are all interesting and worthwhile reading. For the purposes of this article, I am just interested in their narco message datasets.

There are a number of caveats and limitations to this article. Datasets on narco messages are few. Between data sets, definitions are not nailed down firmly and collection methodologies vary slightly. Despite these difficulties, in this article I aim to arrive at a reasonable estimate through examining all known datasets, and inferring logically what I cannot find for certain.

This article defines narco messages as written or printed physical communications from criminal groups in Mexico, often publicly placed. This includes large sheets (narcomantas), cardboard scrawled messages (narcomensajes), and leaflets (volantes). I aim for a broad, inclusive definition to engage the totality of physical narco messaging used by criminal groups.

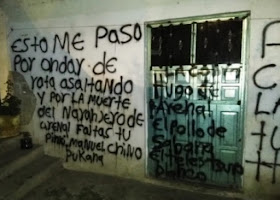

|

| Spraypainted message on the house of the Municipal treasurer of Coxquihui, Veracruz. Source. |

Narco messages found in each study:

Here are the results from six datasets on narco messages I found. All six datasets were collected in a similar manner and use a comparable definition for what constitutes a narco message. For a more expanded look at each data set, skip to the bottom.

Dataset 1 - CIDE, Laura Atuesta

Narco messages without bodies per year:

2008:

281

2009:

506

2010:

889

2011:

948

Narco messages adjusted for percentage found with bodies:

2007: 105

2008: 525

2009: 946

2010: 1,662

2011: 1,772

Dataset 2 - Carlos Martin

Narco messages between October 2009 and October 2010:

1,419

Dataset 3 - Brian J. Phillips and Viridiana Ríos

Narco messages between 2007 and 2010:

1,800

No

breakdown by year.

Dataset 4 - Philip Luke Johnson

Narco messages between 2006 and 2013:

4,000+

No

breakdown by year.

Dataset 5 - Günther Maihold

Narco messages between June 2007 and October

27, 2008:

2,061

Same rate for 12-month period:

1,455

Dataset 6 - El Huaso

Narco messages in 2021:

1,114

Quantity

Between the

years of 2007 and 2010, the number of narco messages sharply increased. The

only outlier was Maihold’s data set, which gathered 1,455 messages in a

12-month period in 2008. Given that

Maihold did not explain how his data was found exactly, as well as being a

little unclear on his definition of a narco message, I have excluded his findings

from the conclusion.

After 2010, the number seems to have stabilized at over well over 1,000 narco messages per year. This number was found in Carlos Martin’s data set, CIDE’s, as well as my own. It is far more likely for a data set to undercount than overcount, so I have chosen CIDE's higher numbers for the years 2010 and 2011 over Martins data set.

As a conservative estimate, between the years of 2012 and 2022, it is likely that over 1,400 narco messages were left each year for a total of 14,000 narco messages. The only data publicly available for the years prior to 2012 is CIDE’s and Martin’s data sets. Adjusting for narco messages with bodies, we get 105 in 2007, 525 in 2008, and 946 in 2009, 1,662 in 2010, 1,772 in 2011, for a total of 5,010 narco messages. Adding these to the 14,000 between 2012 and 2022, we get a total of at least 19,010 messages since 2007.

2007: 105

2008: 525

2009: 946

2010: 1,662

2011: 1,772

2012:

1,400

2013:

1,400

2014:

1,400

2015:

1,400

2016:

1,400

2017:

1,400

2018:

1,400

2019:

1,400

2020:

1,400

2021:

1,400

2022:

1,400

Common themes between datasets

There is a lack of information for the latter half of the 2010s and start of the 2020s. Most information we have about narco messages was collected by the Mexican government and leaked. To my knowledge there are very few if any researchers currently gathering this information.

Phillips and Rios also mention how the Mexican

news media restricted their own coverage of narco messaging and violence after

2011, which may lead to undercount in messaging from 2011 onwards. While this

is true, I think that the independent media, such as Twitter accounts and nota

roja pages have filled the information gap, and the media blackout on messaging

may not be as large of a factor as previously thought.

All data sets agree on several conclusions regarding quantity. First, the number of narco messages found in Mexico has increased overtime. While there are a few scattered examples of narco messaging prior to 2007, it seems that criminal groups began using narco messages on a large scale in the late 2000s. The number of messages deployed annually exploded in the following years.

Further, based on the quantity of messages, all datasets point to physical narco messages being the primary form of communication from criminal groups in Mexico. While other methods of communication are utilized, such as scripted video messages or airdropped leaflets, no other method of communication comes close to the quantity of physical narco messages deployed.

Also, all data sets show that messages are used in most Mexican states.

Reasons for the lack of narco

message data sets

Part of the reason for the lack of comprehensive data sets on narco messaging is the general perception of the limited utility in studying them. I have spoken to researchers who argued that it is nearly impossible to determine who was really behind a narco message. Indeed, Maihold argues that police forces have used narco messages to “self-legitimize the corporations”.

Further, given the quantity of narco messages, creating a large data set is time and energy intensive, making it infeasible for many research teams.

Also, for some studies, finding the exact number of narco messages left in a year is irrelevant as they focus on discourse analysis, or how the communications are used. For these, the researchers randomly select a certain number of messages to study from a larger data set or choose specific notable communications.

|

| CJNG narco banners in Guanajuato. Source. |

Expanded look at the data sets

The first dataset - Mexican Government leak to CIDE, Laura Atuesta (2007 - 2010)

The first major database was leaked from a

Mexican government database to the Center for Research and Teaching in

Economics (CIDE), a university and think tank in Mexico City. This dataset

contains 2,680 narco messages between 2007 and 2011.

In ‘Narcomessages as a way to analyse the evolution of organised crime in Mexico’, Dr. Atuesta borrows a definition of narco messages from organized crime scholar Viridiana Rios, writing that they are “billboards that traffickers leave on the streets to clarify why they assassinated someone, to intimidate other potential victims, identify themselves or their victims, communicate with citizens around the area, or give instructions to the investigators who will eventually record the messages, among other reasons”.[8]

There is one major caveat - this data set only includes narco messages that were left next to a body.[9] Therefore, the data set excludes all narco messages that were hung from bridges, or simply left without a corpse. Based on two other data sets we will explore later, this excludes about half of narco messages.

The sixth dataset, which I collected, found that 54.12% of messages were found next to bodies. This finding aligns with that of dataset two by Carlos Martin, which found that 53% were found next to bodies. If we take the average of these two, we can estimate that 53.5% of narco messages are left next to bodies. Using this figure, we can multiply estimate the true number of narco messages between 2007 and 2011, as the CIDE dataset only included messages found next to bodies.

Where Y is narco messages with bodies, and X is narco messages without bodies.

Y/X = 53.5/100

X=1,772

The amended data is therefore:

2007: 105

2008: 525

2009: 946

2010: 1,662

2011: 1,772

There are some caveats. This assumes that the number of messages with bodies next to them stayed constant throughout the years. Datasets two and six, collected one decade apart with similar collection methodologies, found a very similar proportion of messages left to bodies. However, it is possible that criminal groups did not start leaving bodies at such higher rates until 2010. Beheadings for example, were not always as common in Mexico as they are now. They became a criminal fashion and spread across Mexico in the first years of Mexico’s drug war, increasing from 32 in 2007 up to 493 in 2011, according to Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office. [10]

Laura H.

Atuesta (2017) Narcomessages as a way to analyse the evolution of organised

crime in Mexico, Global Crime, 18:2, 100-121, DOI:

10.1080/17440572.2016.1248556

The second dataset - Carlos Martin (2010)

The next data set is from an academic article by Carlos Martin titled “Categorization of Narcomessages in Mexico: An Appraisal of the Attempts to Influence Public Perception and Policy Actions”. This data set was collected using a vast search through open sources between October 2009 and October 2010, finding 1,419 narco messages across 31 Mexican states.

Martin argues that narco messages are used by criminal groups in Mexico to “influence public opinion” and can” illuminate the interests behind the actions of the cartels”. He uses a broad definition, writing that they “usually appear in the form of cardboard messages left on executed bodies, banners hung from bridges and traffic lights, or as graffiti written on walls” but can also include messages written on t-shirts of bodies. [11]

Carlos

Martin (2012) Categorization of Narcomessages in Mexico: An Appraisal of the

Attempts to Influence Public Perception and Policy Actions, Studies in Conflict

& Terrorism, 35:1, 76-93, DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2012.631459

The third dataset - Brian J.

Phillips and Viridiana Ríos (2007 - 2010)

In ‘Narco-Messages: Competition and Public Communication by Criminal Groups’, researchers Brian J. Phillips and Viridiana Ríos examined the circumstances around narco messages, which they define as "narco-messages are texts left by criminal organizations in a public place to communicate with other criminal groups, the public, or authorities".[12] They used a data set of 1,800 narco messages found by open-source searches between 2007 and 2010. They do not specify how many were found each year, unfortunately.

Compared to other datasets, their numbers are low. While spanning the same years as the data used by CIDE, their dataset has 1,800 messages to CIDE’s 2,680. They wrote that “When a message contained the same text and was displayed in the same municipality around the same date, we assumed that it could be duplicated coverage.” It is possible that this also meant they undercounted messages by missing messaging campaigns where multiple identical messages were deployed, as criminal groups often do. For example, in the state of Guanajuato, the CJNG Grupo Elite faction frequently employs message campaigns, leaving large quantities of the identical banner around the state, as reported by Borderland Beat.

Phillips,

B., & Ríos, V. (2020). Narco-Messages: Competition and Public Communication

by Criminal Groups. Latin American Politics and Society, 62(1), 1-24.

doi:10.1017/lap.2019.43

The fourth dataset - Dr. Philip Luke Johnson (2007 - 2013)

Another researcher whose work I have been following with great interest is Dr. Philip Luke Johnson of Princeton University. He has collected narco messages on his own for an upcoming paper and book on the topic. While he has not released his data set yet, he does reference it on his personal website. Johnson collected his dataset through manual searches on major Mexican news sites such as Proceso and Noroeste.[13]

He wrote in 2018 that his database of messages left between 2006 and 2013 passed 4,000 messages. However, his data set is unpublished and we do not know how many were left per year.

Luke

Johnson, Philip. “CPW 10/3/18 - Johnson on Narco-Messages and the Legibility of

Violence - Political Science | the Graduate Center, CUNY.” Political Science |

the Graduate Center, CUNY, 3 Oct. 2018,

politicalscience.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2018/10/03/cpw-10-3-18-johnson-on-narco-messages-and-the-legibility-of-violence/.

The fifth dataset - Günther Maihold (June 2007 - October 27, 2008)

Günther Maihold wrote in a 2012 article titled “Criminal communications: The case of narco banners” that between June 2007 and October 27, 2008, a 17 -month period, he found 2,061 narco messages in Mexico.[14] Dividing his findings to reach a 12-month number, we get 1,455 narco messages. This figure is perplexing, as it is much higher than the CIDE dataset for the same years. Even comparing Maihold’s dataset for a 17-month period (2,061) with CIDE’s 24-month period 337, Maihold’s dataset dwarfs CIDE’s by a factor of six.

Maihold argues that narcomantas, or narco banners in English, are “publicity efforts from cartels who place them in public places - for example, on sidewalks - with the goal of attracting the attention of civil society and the news media in order to reproduce and divulge, and by that manner generate an alternative discourse to the communications of government actors”.

Maihold,

Günther. Las Comunicaciones Criminales: El Caso De Las Narcomantas. : Colectivo

de Análisis de la Seguridad con Democracia, 2012.

https://www.casede.org/PublicacionesCasede/Atlas2012/GUNTHER_MAIHOLD.pdf

The sixth dataset - El Huaso (2021)

The final data set is one collected by myself. This data set includes 1,114 messages left in Mexico between January 1, 2021, and December 29, 2021. This data set was collected by searching for relevant keywords in Google news, Twitter, and on several Mexican news websites such as Proceso and Valor por Tamaulipas.

These narco banners were found in over 300 different municipalities in Mexico, were signed by 249 different criminal actors, and communicated with everyone from rival drug dealers to the president himself. In results, my dataset aligns closely with dataset 2 by Carlos Martin.

Works Cited

[1] Phillips, Brian J., and Viridiana Ríos.

“Narco-Messages: Competition and Public Communication by Criminal Groups.”

Latin American Politics and Society, vol. 62, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–24.,

doi:10.1017/lap.2019.43.

[3] “La Familia Michoacana, Temible Cartel Del Narcotráfico, Entre La Biblia Y La Ferocidad Extrema.” El Tiempo, El Tiempo, 18 July 2009, www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-5649388.

[4] Ibid.

[5]Alvarado, Ignacio. “Mensajes Macabros, La Nueva Herramienta de Los Capos En México.” U.S., 25 June 2008, www.reuters.com/article/latinoamerica-delito-mexico-narcotrafico-idLTAN2526171320080625.

[6] Luke Johnson, Philip. “CPW 10/3/18 - Johnson on Narco-Messages and the Legibility of Violence - Political Science | the Graduate Center, CUNY.” Political Science | the Graduate Center, CUNY, 3 Oct. 2018, politicalscience.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2018/10/03/cpw-10-3-18-johnson-on-narco-messages-and-the-legibility-of-violence/.

[7] Laura H. Atuesta (2017) Narcomessages as a

way to analyse the evolution of organised crime in Mexico, Global Crime, 18:2,

100-121, DOI: 10.1080/17440572.2016.1248556

[9] Laura H. Atuesta (2017) Narcomessages as a way to analyse the evolution of organised crime in Mexico, Global Crime, 18:2, 100-121, DOI: 10.1080/17440572.2016.1248556

[10] Pachico, Elyssa. “Tracking the Steady Rise of Beheadings in Mexico.” InSight Crime, 27 Mar. 2017, insightcrime.org/news/analysis/tracking-the-steady-rise-of-beheadings-in-mexico/#:~:text=According%20to%20Mexico’s%20Attorney%20General’s,war%20between%20the%20country’s%20cartels.

[11] Carlos Martin (2012) Categorization of Narcomessages in Mexico: An Appraisal of the Attempts to Influence Public Perception and Policy Actions, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 35:1, 76-93, DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2012.631459

[12] Phillips, B., & Ríos, V. (2020).

Narco-Messages: Competition and Public Communication by Criminal Groups. Latin

American Politics and Society, 62(1), 1-24. doi:10.1017/lap.2019.43

[13] “The Deaths behind the Data.” Philip Luke Johnson, Philip Luke Johnson, 9 June 2018, philipljohnson.com/2018/06/09/i-had-not-thought-death-had-undone-so-many/..

[14] Maihold, Günther. Las Comunicaciones Criminales: El Caso De Las Narcomantas. : Colectivo de Análisis de la Seguridad con Democracia, 2012.

https://www.casede.org/PublicacionesCasede/Atlas2012/GUNTHER_MAIHOLD.pdf

I estimate that at least 1,400 narco messages are left in Mexico each year, or almost 20,000 since the beginning of the drug war.

ReplyDeleteWhat do you think of my numbers?

I think these are the kind of analysis needed in the field of Mexican organized crime investigations. The fact that Borderland Beat has come to the point of offering such level of detailed statistics reveals the kind of incredible work you´ve brought with you compa. Mis dieses Huaso!!

DeleteHow effective are they? Honestly, it’s so over done that they seems pointless. Just like narco videos. They always mention the same thing “esto me pasó por…” or “venimos a limpiar de…”

ReplyDeleteIt's a good question. Tough to know. They certainly cause unease and fear. A friend of mine almost crashed her car when she saw one in her neighborhood once.

DeleteI am writing another paper examining one event and how the government's response to it was shaped by narco communications. In that event I think they were very effective.

I’ve been wondering this myself… my opinion is they have lost their shock value, and overall impact…

Delete